Introduction

John Mundy’s settings of Dum transisset Sabatum and De lamentacione survive exclusively in the Baldwin partbooks (GB-Och Mus 979–983). Originally a set of six, the Baldwin partbooks preserve a wealth of musical material from both before and after the English Reformation. However, the tenor volume is missing, leaving much of the repertory incomplete. Some music has concordances or can be completed by inserting plainsong or faburden, but around 100 of the 160 pieces still require an editorial reconstruction of the tenor part in order to be performable. These two pieces by Mundy fall into this later category.

Both pieces are distinctive. Dum transisset Sabatum was entered into the partbooks after the main phase of copying had ended, while De lamentacione, despite its title, is not a setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah but a prayer against schism, the main text of which derives from Jean de Bruges’s De Veritate Astronomiae. These unusual works are significant not only because they survive in incomplete form but also because they reveal Mundy as a composer deeply engaged with the styles and techniques of the previous generation.

John Mundy

John Mundy, son of the composer William Mundy, was part of a distinguished musical family. Born around 1555, he was educated as a chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral in London, where his father was employed. By 1585 he had taken the degree of Bachelor of Music at Oxford, and later, in 1624, he was awarded a Doctor of Music.

Mundy spent most of his career at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where he served as organist and Master of the Choristers. In 1585 he succeeded John Marbeck in this post and remained there until his death. He was also appointed a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, which placed him among the leading professional musicians of his generation. His presence at Windsor brought him into the same circle as John Baldwin, a lay clerk and copyist, who compiled the Baldwin partbooks. It is almost certainly through this connection that Mundy’s works, including Dum transisset Sabatum and De lamentacione, entered Baldwin’s collection.

Mundy died in 1630 and was buried in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where he had served for nearly half a century. Though his name is less well-known today than that of Tallis or Byrd, he was a respected figure in his own time, admired for maintaining the rich traditions of English church music into the early Stuart era.

A composer in touch with

the previous generation

The compositions that will be performed in The Old Science of Sound give the impression of a composer deeply engaged with the stylistic inheritance of the preceding generation. Both works appear to make frequent reference to settings of the same, or closely related, texts by earlier composers, in ways that seem too consistent to be coincidental. John Mundy’s father, William Mundy, was himself a composer of distinction and a member of the Chapel Royal. It may have been through this familial connection, or through other aspects of his otherwise undocumented musical training, that John Mundy became acquainted with the repertory he appears to emulate, whether consciously or subconsciously.

Dum transisset Sabatum

The influence of earlier composers is particularly apparent at the opening of this work. The fuga (strict imitation) employed by Mundy in the first entry bears a striking resemblance to that used by Thomas Tallis in his own setting of the same text, preserved in Cantiones Sacrae (1575). As Figures 1a and 1b illustrate, the rhythmic similarity between the two settings is unmistakable, while melodically Mundy’s treatment essentially inverts the second half of Tallis’s ‘sabatum’ motif. Tallis’s fuga is more consistent, as might be expected of a composer of his stature, but the parallels remain noteworthy, especially given that other settings of the same text avoid such close resemblance.

Dum transisset Sabbatum (ed. David Fraser).

Further points of comparison can be found in the ‘aromata’ section (bars 33–45). Here, Mundy’s melodic and rhythmic writing strongly recalls the cantus firmus settings of John Taverner (see Figures 2a and 2b). Both composers employ a rising and falling contour before the text repetition, although Mundy extends his motif further. The similarity is nevertheless sufficiently marked to suggest deliberate imitation.

five-part Dum transisset Sabatum (ed. Adrian Wall).

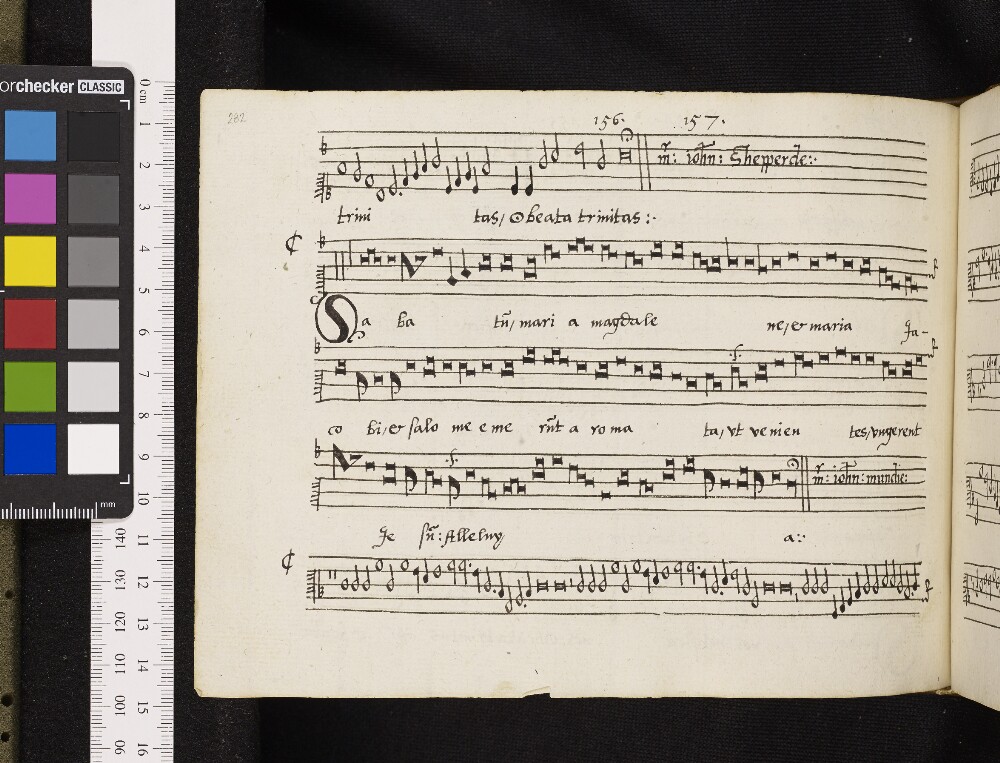

John Sheppard’s second setting of Dum transisset Sabatum (also preserved in the Baldwin partbooks) appears to have provided another model. Mundy’s setting of the word ‘ungerent’ exhibits rhythmic similarities to Sheppard’s, with the same prosodic stress shaping the musical line (Figures 3a and 3b). Although not as striking as the Tallis and Taverner parallels, this resemblance again suggests that Mundy was engaging with earlier treatments of the text.

second setting of Dum transisset Sabatum (ed. Jason Smart).

A further notable comparison occurs in the closing ‘alleluya’, where Mundy’s spacing of voices closely echoes that of Taverner’s five-part setting (Figures 4a and 4b). Both composers employ A minor chords with the third in the highest part and an E in the second-highest voice. My editorial tenor part, beginning on E, reinforces this similarity, though even if the tenor were placed on A, Mundy’s overall sonority remains strikingly close to Taverner’s. The resemblance is particularly evident in the staggered entries of the contratenor and second bass, which create a buoyant effect while preserving Taverner’s harmonic outline.

Dum transisset Sabatum.

Taken together, these similarities suggest Dum transisset Sabatum functions almost as a sequence of allusions to his antecedents. In some instances, the resemblance is more overt (particularly in the opening fuga) and it is plausible to view the work as a conscious act of homage. Quotation of this kind was an established compositional strategy, often extended by the addition of an extra voice, which could signal respect and admiration rather than rivalry or disdain. Mundy’s setting may therefore be understood less as a display of technical innovation and more as a deliberate engagement with his musical forebears.

De lamentacione

Mundy’s De lamentacione setting is not, in fact, a setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah. Instead, it is based primarily on a prayer against schism from Jean de Bruges’s De Veritate Astronomiae, a text that may have reached Mundy through Tielman Susato’s Liber quartussacrarum cantionum (1547). To this he appended the opening incipit De lamentacione, Jeremie prophete, together with verses from Zephaniah 1:14, Psalm 121 (122), and Hebrew letters (the full text is given below). This eclectic construction produces a text of unusual character, unlikely to have been suitable for liturgical use in the Tenebrae service. The inclusion of the incipit and Hebrew letters may instead reflect a desire to place the work within the tradition of polyphonic De lamentatione settings cultivated by English composers such as Tallis, White, and Byrd. The thematic focus on a prayer against schism might conceivably have appealed to recusant Catholic communities. Yet there is no evidence that Mundy himself was a recusant or that his music circulated in such circles. None of his works, for example, appear in the Paston manuscripts or the Sadler partbooks. It is therefore more likely that the piece was intended for private performance, although the intended audience remains unknown.

As in Dum transisset Sabatum, Mundy again appears to look to earlier models. At bar 38, the imitative duo recalls the fuga Tallis employed in the second part of his celebrated Lamentations, particularly on the text ‘omnes persecutores’ (Figures 5a and 5b). Whether coincidental or not, the similarity highlights Mundy’s adoption of contrapuntal strategies associated with the preceding generation.

which may have influenced Mundy (ed. Carlos Rodríguez Otero).

The influence of Tallis seems to appear yet again from bars 59–85 starting on the word ‘Jerusalem’. In this section, Mundy’s highest voice (with two exceptions in bars 64 and 66) pre-empts the rest of the choir by two beats who then join in below in homophony. This is reminiscent of the beautiful passage in Tallis’s Lamentations where, again, the upper voices sings the word ‘Jerusalem’ two beats before the rest of the choir (see Figures 6a and 6b). While this sort of staggered homophony occurs frequently in this repertory, the fact that it happens in the highest voice and starting on the word ‘Jerusalem’ seems to show the influence of Tallis on John Mundy.

Concluding thoughts

The influence of earlier composers is evident throughout both works examined here. Numerous parallels suggest conscious quotation or imitation rather than mere coincidence. Mundy’s indebtedness to Tallis, Taverner, and Sheppard positions him as a composer whose creative identity was shaped by the stylistic practices of his predecessors. His familial connections through his father William, and his professional associations within the Chapel Royal, would have facilitated access to this repertory. David Mateer’s description of Mundy’s ‘conservative output’ in The New Grove Dictionary is borne out by these examples: Mundy’s Latin church music is not innovative or groundbreaking; instead, it situates itself firmly within the established traditions of the previous generation.

De lamentacione Jeremie prophete.

Daleth.

Juxta est dies Domini,

[juxta] est et velox nimis,

rogate que ad pacem sunt, Jerusalem,

et ecclesiam iam dolentem confortate,

iam errantem informate,

iam divisam integrate,

naufragantem ad portum reducite,

ne fiat illud schisma magnum

quod praeambulum erit Antechristi.

Lamed.

In cuius ad ventum de ecclesia,

verificabitur illud jeremie prophete,

omnes porte eius destructe,

sacerdotes eius gementes,

virgines eius squalide,

et ipsa oppressa amaritudine,

tunc petri navicula

schismatico turbine diutius agitata,

dissipatur in proximo submergenda.

From the lamentations of Jeremiah the prophet.

Daleth.

The day of the Lord is at hand,

it is near and exceeding swift.

O pray for the peace of Jerusalem: […]

and comfort thy Church that is now grieving;

instruct it, that is now in error;

put it back together that is now divided;

lead it back to port that is now shipwrecked,

so that this should not lead to a great schism,

which will herald the coming of the Antichrist.

Lamed.

At whose coming the saying of the prophet Jeremiah

about the church shall be made true:

all her gates are ruined,

her priests groan,

her virgins are in rags,

and she is overwhelmed with bitterness.

Then the little ship of Peter,

tossed about for too long in the storm of the schism,

is split apart, ready soon to sink.

Leave a comment