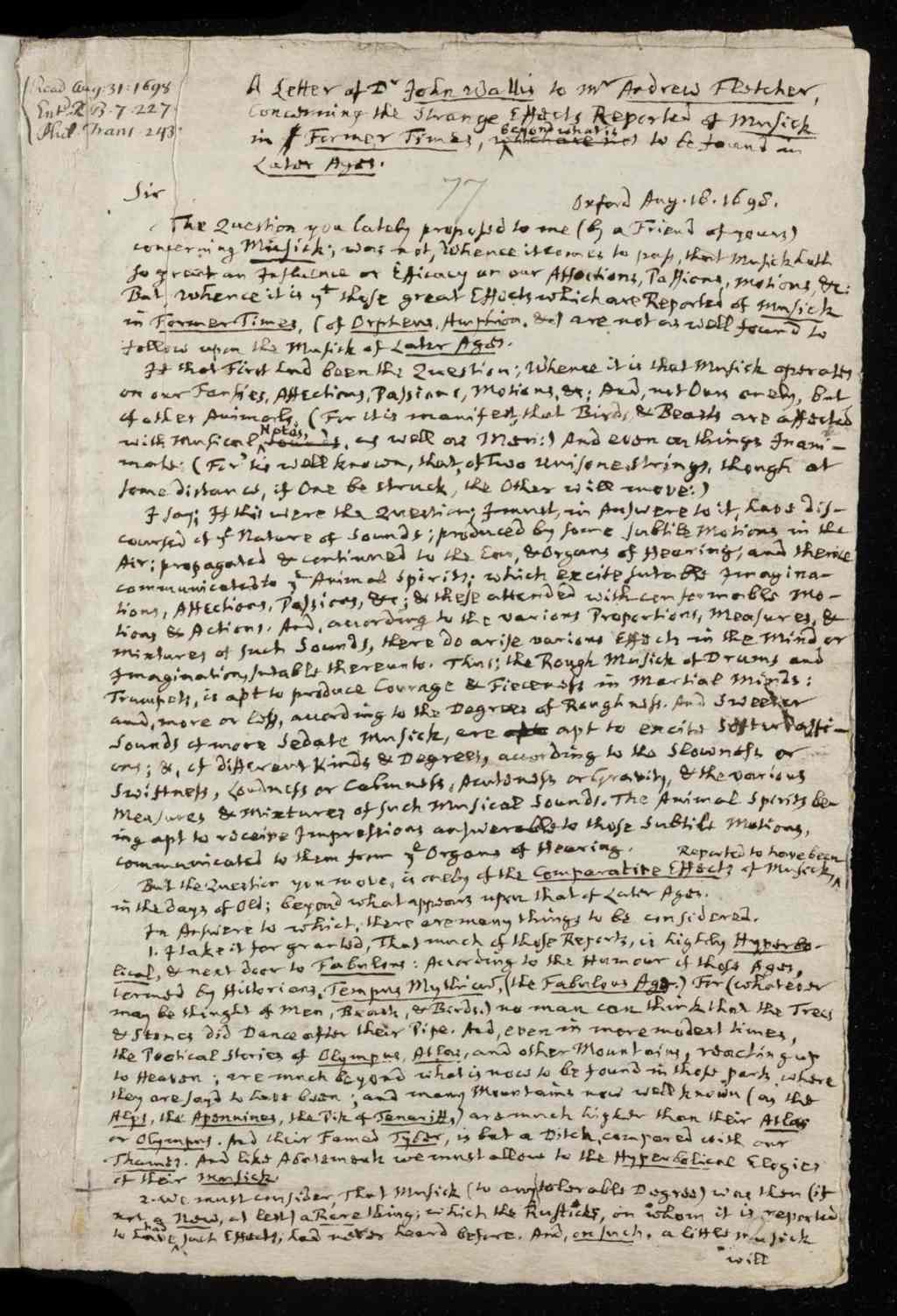

A Letter of Dr John Wallis to Mr Andrew Fletcher, Concerning the Strange Effects Reported of Musick in Former Times, ⟨beyond what is⟩ to be found in Later Ages.

Oxford Aug. 18. 1698.

Sir

The Question you lately proposed to me (by a Friend of yours) concerning Musick; was not, Whence it comes to pass, that Musick hath so great an Influence or Efficacy on our Affections, Passions, Motions, &c: But, whence it is that these great Effects which are Reported of Musick in Former Times, (of Orpheus, Amphion, &c) are not as well found to follow upon the Musick of Later Ages.

If that First had been the Question; Whence it is that Musick Operates on our Fancies, Affections, Passions, Motions, &c; And, not Ours onely, but of other Animals, (For it is manifest, that Birds, & Beasts are affected with Musical ⟨Notes⟩, as well as Men:) And even as things Inanimate; (For ’tis well known, that, of Two Unisone Strings, though at some distance, if One be struck, the Other will move:)

I say; If this were the Question; I must, in Answere to it, have discoursed of the Nature of Sounds; produced by some Subtile Motions in the Air; propagated & continued to the Ear, & Organs of Hearing; and thence communicated to the Animal Spirits; which excite sutable Imaginations, Affections, Passions, &c; & these attended with conformable Motions & Actions, And, according to the various Proportions, Measures, & Mixtures of such Sounds, there do arise various Effects in the Mind or Imaginations, sutable thereunto. Thus; the Rough Musick of Drums and Trumpets, is apt to produce Courage & Fie[r]ceness in Martial Mind: and, more or less, according to the Degrees of Roughness. And sweeter Sounds of more sedate Musick, are apt to excite softer Passions; &, of different Kinds & Degrees, according to the Slowness or Swiftness, Loudness or Calmness, Acuteness or Gravity, & the various Measures and Mixtures of such Musical Sounds. The Animal Spirits being apt to receive Impressions answerable to those subtile Motions, communicated to them from the Organs of Hearing. But the Question you move, is onely of the Comparative Effects of Musick, ⟨Reported to have been⟩ in the days of Old; beyond what appears upon that of Later Ages.

In Answere to which, there are many things to be considered.

- I take it for granted, That much of those Reports, is highly Hyperbolical, & next door to Fabulous: According to the Humour of those Ages, termed by Historians, Tempus Mythicum, (the Fabulous Age.) For (whatever may be though of Men, Beasts, & Birds.) no man can think that the Trees & Stones did Dance after their Pipe. And, even in more modest times, the Poetical Stories of Olympus, Atlas, and other Mountaines, reaching up to Heaven; are much beyond what is now to be found in those parts, where they are sayd to have been; and many Mountains now well known (as the Alps, the Apennines, the Pik of Tenariff,) are much higher than their Atlas or Olympus. And their Famed Tyber, is but a Ditch, compared with our Thames. And like Abatements we must allow to the Hyperbolical Elogies of their Musick.

- We must consider, That Musick (to any tolerable Degree) was then (if not a New, as lest) a Rare Thing; which the Rusticks, on whom it is reported to have ⟨had⟩ such Effects; had never heard before. And on such, a little musick [fol. 1v] will do great Feats. As we find, at this day; a Fidd[l]e or a Bag-pipe, among a company of Countrey Fellows & Wenches (who never knew better,) or at a Country Morrics Dance; will make them skip & shake their Heeles notably. (And the like, heretofore, to a Shep-herds Reed or Oaten-Pipe.) And, when some such thing ⟨happened⟩ amongst those Rusticks of Old; That, with somewhat of Hyperbole, would make a great Noise.

- We are to consider, that their Musick (even after it came to some good degree of Perfection) was much more Plain & Simple than Ours now a-days. They had not Consorts of Two, Three, Four, or more Parts or Voices: but one single Voice, or single Instrument, a-part; which, to a Rude Ear, is much more taking, than more Compounded Musick. And we find that a simple Jig, sung, or playd on a Fiddle or Bag-pipe, doth more Affect a company of Rusticks, than a sett of Viols & Voices. For, That, is at a pitch not above their Capacity; whereas, This other, confounds it, with a great Noise, but nothing Distingable to their capacity. Like some delicate Sawce, made-up of a mixture of many Ingredients; which may yield an agreeable Tast; but not so as to distinguish the Particular Relish of any one: But Hony or Sugar by itself, they could Understand & Relish with a ⟨more peculiar⟩ Gusto.

- We are to consider, That Musick, with the Ancients, was of a larger extent than what We would call Musick now a-days. For Poetry and Dancing (or Comely Motion,) were then accounted parts of Musick, when Musick arrived to some perfection. Now we know that Verse of it self, if in good Measures, & affectionate Language, & this sett to a Musical Tune, & sung by a decent Voice, & accompanyed but with Soft Musick (instrumental) if any; such as not to Drown or Obscure the Emphatick Expressions, (like what we call Recitative Musick;) will work strangely upon the Ear, & move Affections sutable to ⟨the⟩ Tune & Ditty; (whether Brisk & Pleasant, or Soft & Pityfull, or Fierce & Angry, or Moderate & Sedate:) especially if attended with a Gesture and Action sutable. (For ‘tis well known, that sutable Acting on a Stage, gives great Life to the Words.) Now all this together (which were all Ingredients in what they called Musick) must needs operate strongly on the Fansies & Affections of Ordinary People, unacquainted with such kind of Treatments. For, if the deliberate Reading of a Romance (when well penned) will produce Mirth, Tears, Joy, Grief, Pitty, Wrath, or Indignation, sutable to the respective Intents of it: much more would it so do, if accompanied with all those Attendants.

- You will ask perhaps, Why may not all this be Now done, as well as Then? I answere, No doubt it may; and, with like Effect. If an Address be made, in Proper Words, with Moving Arguments, in Just Measures (Poetical or Rhetorical) with the Accent, and attended with a Decent Gesture; and all these Sutably adjusted to the Passion, Affection, or Temper of Mind, particularly Designed to be produced, (be it Joy, Love, Grief, Pitty, Courage, or Indignation;) will certainly Now, as well as Then, produce great Effects upon the Mind. Especially, upon a Surprize, & where Persons are not otherwise Preingaged: And, if so managed as that you be (or seem to be) in Ernest; and, if not over-acted by apparent Affectation.

- We are to consider, That the Usual Design, of what we now call Musick; is very different from that of the Ancients. What we Now call Musick, is but what they called Harmonick; which was but one Part of their Musick, (consisting of Words, Verse, Voice, Tune, Instruments [fol. 2r] and Acting;) and we are not to expect the same Effect of one Piece, as of the Whole. And, of their Harmonick at first, when we are told (by a great Hyperbole) that it did draw after it, not Men onely, but Birds, Beasts, Trees and Stones: This is no more (bating the Hyperbole,) but what we now see dayly in a Countrey-town; when Boys, & Girls, & Countrey-folk, run after a Bag-pipe or a Fidler, (especially, if they had never seen the like before;) of which we are apt (even now) to say, All the Town runs after the Fidler; or, The Fidler always draws All the Town after him. Or, as when they flock about a Ballad-singer in a Fair; or, the Morrice-dancers at a Whitsund-Ale. And all their Hyp[erb]ole’s can signify no more but this; when their Musick was but a Reed, or an Open-pipe.

- It’s true, that, when Musick was arrived to greater perfection, it was then applyed to particular Designs, of Exciting this or that Particular Affection, Passion, or Temper of Mind; (as Courage, to Souldier[s] in the field; Love, in an Amorous Address; Tears & Pitty, in a Doleful Ditty; Fury & Indignation, in a Fiercer Tune; and a Sedate Temper, when applyed to Compose or Pacify a Furious Quarel;) the Tunes & Measures being sutably Adapted to such Designes.

- But such Designes as these, seem allmost quite Neglected in our present Musick. The chief Designe now, in our most Accomplished Musick, being, to please the Ear. When, by a sweet Mixture of different Parts & Voices, with just Cadences & Concords intermixed, a Gratefull sound is produced, to Please the Ear; (as a Cooks well-tempered Sawce, doth the Palate;) which, to a Common Ear, is onely a confused Noise of they know not what, (though somewhat Pleasing;) while onely the judicious Musician can Discern & Distinguish the just Propoti[ons] (of Time & Tune) which make up this Compound Noise.

- ‘Tis true, that, even this Compound Musick, admits of different Chara[cters;] some is more Brisk & Airy; others, more Sedate & Grave; others, more Languide; as the different Subjects do require. But that which is most proper to Excite particular Passions or Dispositions, is such as is more Simple & Uncompounded: Such as a Nurses languid Tune, lulling her Babe to sleep; or a Continued Reading, in an Even Tone; or even the Soft Murmure of a little Rivulet, running upon Gravel or Pibbles, inducing a Quiet Repose of the Spirits: And, contrarywise, the Briskness of a Jig, on a Kit or Violine, exciting to Dance. Which are more Operative to such Particular Ends, that an Elaborate Composition of Full Musick. Which two, Differ as much, as that of a Cooks mixing a Sawce to make it Palatable; and, that of a Physician, mixing a Potion, for Curing a particular Distemper, or Procuring a just Habit of Body (where yet, a little Sugar to Sweeten it, may not do amiss.)

- To conclude then; If we aim onely at Pleasing the Eare, by a Sweet Consort; I doubt not but our Modern Compositions, may Equal, if not Exceed, those of the Ancients. Amongst whom I do not find any footsteps of what we call several Parts or Voices, (as Bass, Treble, Mean, &c sung in Consort.) answering each other to Compleat the Musick. But if we would have our Musick so adjusted, as to Excite particular Passions, Affections, or Temper of Mind, (as that of the Ancients is supposed to have done;) We must then imitate the Physician, rather than the Cook; and apply more Simple Ingredients, fitted to the Temper we would produce. For, in the Sweet Mixture of Compounded Musick, One thing doth so Correct Another, that it doth not Operate strongly any one way. And this I doubt ⟨not⟩ but a Judicious Composer may so Effect, that (with the help of such Hyperbole’s, as those with which the Ancient Musick is wont to be sett-off) Our Musick may be sayd to do as great Feats, as any of theirs.

I am,

Sir,

Your very humble Servant,

John Wallis.

Oxford Sept. 5. 1698.

Sir

I sent you lately the Copy of a Letter of mine to Mr Andrew Fletcher, relating to Musick. If you think it worth printing, you may adde to it this Post-Scrip[t].

Post-script. Aug. 27. 1698.

Sir

If I did mis-take your Directions by D.G. and have over-done what was desired; pray excuse me that fault. If (as you now intimate) you intended particularly; How, what the Ancients called Musick, (under which you allow to be comprehended Poetry, and (⟨Dancing, that is,⟩ comely Gesture & decent Actions,) might be of such good use in Education (as Aristotle in his Politicks, & Plato in some of his Works, so intimate;) influencing men to Virtue, and directing their Morals & Conversation: I think it is sufficiently answered at numb. 5. 7. 10. For, if such an Address as is there mentioned at numb. 4. 5. be so managed as that the Discourse be Grave & sober; exciting to Virtue & discouraging Vice; and so Attended as is there intimated: No doubt but such Addresses would be strongly Operative that way. (Their Design therein being much the same with that of our Sermons & Religious Exhortations.) But if, in stead thereof, Lewdness & Immoralities be Represented on the Stage; and sett-off with all the Advantages & Incentives thereunto: it is not strange if the Effect be quite Contrary to that other. But the fault is not in the nature of Paranetick ⟨or⟩ Recitative Musick: but in the Mis-application of it to Contrary Purposes. Which I thought fit to adde, in answere to yours of Aug. 25. And am,

Sir,

Your very humble servant,

John Wallis.

[London, Royal Society, MS Early Letters W2, Nos. 77 & 78, fols. 1r/a & 1r/c]

Wallis, John, in:

Philosophical Transactions (1683–1775)

Vol. 20 (1698), pp. 297–303.

Cram, David & Wardhaugh, Benjamin (eds.)

John Wallis: Writings on Music

Music Theory in Britain, 1500–1700: Critical Editions

Farnham: Ashgate, 2014, pp. 223–230.

Leave a comment